From October 25 to November 3, the Davidson College Theater Department will perform William Shakespeare’s tragedy Macbeth. Standing at the crossroads of visual and performing art, the Galleries will decorate Cunningham Hall with various Shakespearean prints in preparation for the big show! These prints date to late-18th Century England, and cover the entire repertoire of the Bard – tragedies, comedies, and histories alike. Perhaps as interesting as the art itself is the history of these prints, filled with high-society fashion, economics, and British nationalism.

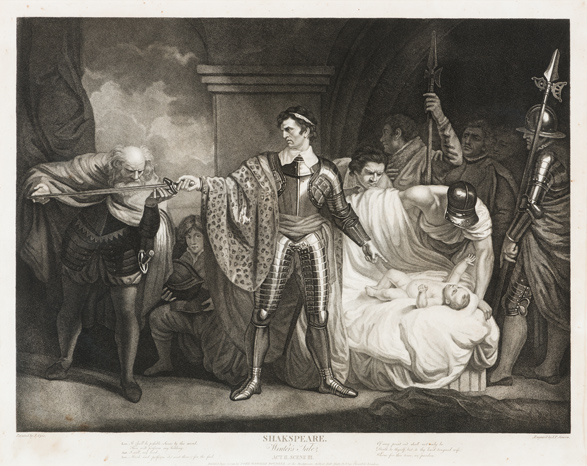

Although Shakespeare died in 1616, by the end of the 18th Century he was enjoying a rising tide of posthumous popularity in England. Symbolizing British culture at a time of high national pride, the Bard’s works saw a renaissance of sorts among all British citizens. Furthermore, the upper echelons of London society used their affinity for Shakespeare to show off their refined, fashionable tastes. The engravings that the Davidson Galleries own represent the peak of 1790’s Shakespeare mania. The mastermind behind this series of prints was publisher John Boydell, who in 1789 opened the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery in London. Boydell sought out well-respected British artists of the time to paint Shakespearean scenes – Richard Westall and John Opie’s names stand out. Lesser-known artists then made engravings based on these paintings. (Westall painted King Henry VIII – Act IV, Scene II, and Opie painted The First Part of King Henry VI – Act II, Scene III, engravings of which are on display now.)

Boydell had his contemporary admirers as well as his critics. Admirers credited him with engineering a touching tribute to the Bard and asserting the superiority of the English school of painters. Detractors criticized Boydell as a greedy entrepreneur, selling out the spirit of Shakespeare’s plays to make a quick buck at his gallery. Although the Shakespeare Gallery had a strong opening, the economic boom and public fervor for Shakespeare died down within the decade. The detractors claimed victory when Boydell’s business folded in 1804. You could put on an economics hat and characterize the downfall of the Shakespeare Gallery as a classic (if abbreviated) cycle of boom and bust. You could put on a historian hat and note how the contemporary revolution in France cut off Boydell from European markets. But perhaps the most interesting hat to don is that of an art historian.

Art historians would note that these engravings used both line engraving and stipple engraving, the latter of which had fallen out of public favor in 18th Century England. Some even used a mixture of the two! Line engraving tends to produce sharper, clearer contours, while stipple engraving produces shading effects and smoother gradients. Art historians would also note that the Shakespeare Gallery used stipple engraving more and more as time went on, since it was a quicker technique. And because the public favored line engraving, an art historian might conjecture that this stylistic difference, not other economic factors, was the greatest reason for the Shakespeare Gallery’s decline.

But, as is often the case in art history, we must keep in mind that contemporary disfavor rarely equates to objective artistic value. As you peruse these prints, see if you can differentiate between the engraving styles. Do you like sharper contour lines? Or smooth transitions from black to grey to white? See if you prefer the earlier or later editions. Would you have had the same taste as 1790’s Englishmen? Or not? Art and theater are timeless, and even though 21st Century America lacks the Shakespeare fervor and aesthetic tastes that 18th Century England possessed, we can enjoy these prints – and Davidson’s production of Macbeth – all the same.